Canada's Ellis Island/La Ellis Island canadese

Inside Pier 21’s rooms/Nelle stanze del Pier 21

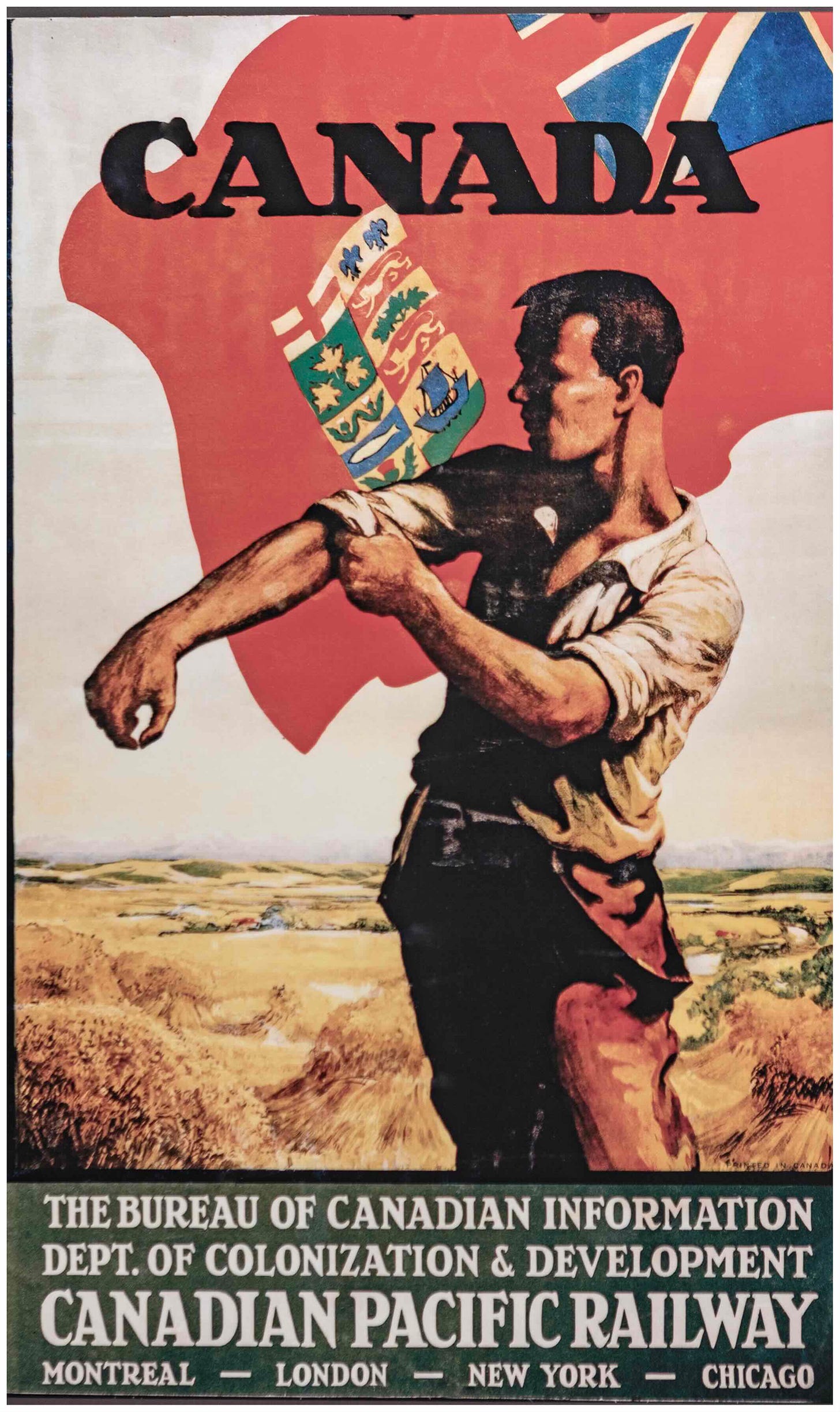

As immigrants to Canada ourselves, we found walking into Halifax’s Pier 21 a rather odd experience. The setting offered by what is now the Canadian Museum of Immigration, in the capital of Nova Scotia, felt at once familiar and profoundly alien. The steps and procedures for obtaining landed immigrant status in the early decades of the 20th century, as outlined on the exhibit panels, weren’t so different from those we followed fifteen years ago—sealed with the dull thump of a stamp on our passports at Vancouver airport.

But the historical circumstances, the atmosphere, and—above all—the emotional state of those who once passed through the rooms of Pier 21 could not have been more different from our own.

For us, immigrating to Canada was a deliberate, well-reasoned decision, taken after a forty-day exploratory visit and gigabytes of research downloaded from the web. We disembarked from a plane ahead of a container filled with furniture and belongings from our former home in Australia. We had resources and credentials that, despite the challenge of starting from scratch and the sadness every migrant feels when leaving behind loved ones, gave us the reasonable confidence that we would soon find our footing—for our sake and, above all, for our children—in this new country we had chosen.

The impression you’re left with, as you walk through those Museum galleries, is of an entirely different kind. The photographs, videos, testimonies, and written accounts—evoke images of extremely poor and often illiterate people disembarking after ten to fourteen days of grueling sea travel (in small eight-berth cabins with a single washbasin, and shared latrines used by dozens of others), unsure of what awaited them, carrying suitcases sometimes literally made of cardboard, with little or no knowledge of the language or culture of the country that was to become their new home. They queued, packed shoulder to shoulder, waiting to undergo a barrage of questions from immigration officers (assisted by volunteer interpreters)—fully aware that a single wrong answer could mean being turned away from the land of new opportunities.

As an Italian, there is something else that can’t escape notice. The many Rolls of Honour displayed on the museum’s walls show that Italians made up one of the largest groups to pass through Pier 21 between 1928 and 1971. During that period, nearly one million people entered Canada via that gangway connecting the ship’s deck to what was then known as the “Gateway”—now just a blank, anonymous wall, stripped of all visible traces of the lives that once crossed it.

And yet, some of those lives still return. One such case was recounted to us by the museum curator—visibly moved—who guided our visit. Just a few months earlier, an elderly woman had come through the museum. While slowly scanning the photos displayed on the walls, she stopped in front of one in particular: it showed a woman with a small child in her arms, stepping onto the footway leading to the Gateway. The woman in the photo was her mother. The child in her arms was herself—seventy-five years ago.

La Ellis Island canadese

Entrare nel Pier 21 di Halifax, da immigrati in Canada quali siamo anche noi, è stata un’esperienza straniante. Il contesto evocato da quello che oggi è il Museo Canadese dell’Immigrazione nella capitale della Nova Scotia, ci è apparso familiare ma anche profondamente distante. L’iter e molte delle procedure per acquisire lo status di landed immigrant nei primi decenni del Novecento, illustrati nei pannelli espositivi, non sono poi così diversi da quelli da noi seguiti oltre quindici anni fa e conclusisi con il sordo tonfo di un timbro apposto sui nostri passaporti all’aeroporto di Vancouver.

Ma le circostanze, l’atmosfera e, non da ultimo, lo stato d’animo di quanti passarono per quegli ambienti allora, non potrebbero essere più lontani da ciò che abbiamo vissuto noi.

Per noi, immigrare in Canada è stata una scelta ragionata e calcolata, presa dopo una visita esplorativa di quaranta giorni e gigabyte di informazioni scaricati dalla rete. Siamo scesi da un aereo precedendo di poco l’arrivo di un container pieno di mobilio e masserizie in arrivo dalla nostra precedente casa in Australia. Avevamo mezzi e titoli che, pur nella difficoltà del dover ricominciare da capo e nella tristezza che ogni migrante prova nel lasciare familiari e amici, ci davano la fondata fiducia di poter acquisire una condizione di stabilità—per noi e, soprattutto, per i nostri figli—nella società in cui avevamo scelto di vivere.

La sensazione che invece si ricava transitando per le sale del museo è di tutt’altro tenore: le fotografie, i filmati, le testimonianze scritte suggeriscono immagini di persone povere, spesso analfabete, sbarcate dopo dieci – a volte quattordici – durissimi giorni in mare (in piccole cuccette da otto posti con un solo lavabo, latrine comuni condivise con decine di altri), ignare di quanto le attendeva, con valigie spesso letteralmente di cartone e poca o nessuna conoscenza della lingua e dei costumi del paese che le avrebbe accolte. Accalcate in fila, fianco a fianco, attendevano di essere sottoposte a un fuoco di fila di domande da parte degli ufficiali dell’immigrazione (talvolta assistiti da interpreti volontari), sapendo che una sola risposta sbagliata avrebbe potuto negare loro l’accesso alla terra delle nuove opportunità.

Per un italiano, c’è un altro dettaglio che non passa inosservato. Come si deduce dai tanti Albi d’onore affissi alle pareti del museo, i nostri connazionali rappresentano uno dei gruppi più numerosi tra coloro che passarono per il Pier 21 tra il 1928 e il 1971. In quel periodo, furono quasi un milione i migranti che entrarono in Canada attraversando la passerella sospesa tra il ponte della nave e quello che allora era chiamato il Gateway—oggi ridotto a una parete anonima, spoglia di ogni traccia visibile delle vite che l’hanno attraversata.

Eppure, alcune di quelle vite ogni tanto ritornano. Lo ha raccontato—visibilmente commossa—la curatrice che ci ha accompagnati nella visita. Qualche mese fa, un’anziana signora si aggirava tra le sale del museo; mentre passava in rassegna le foto appese alle pareti, si è fermata di colpo davanti a una in particolare: ritraeva una donna con una bambina in braccio nell’atto di imboccare la passerella verso il Gateway. La donna nella foto era sua madre. La bambina, lei stessa—settantacinque anni prima.

HI again....just did a bit of research (your inspiration) and found out grandparents from Udine came via Le Havre, France to Ellis Island on ship called La Lorraine. This was in 1910. They then were processed into Canada at Port of Quebec City. Not sure how they got there, but.....

Thank you from Rome, Italy. My partner and I made it a point to visit Pier 21 during our trip to Canada to see my brothers a couple of years ago, so it was really interesting to read this piece and recall the emotional experience of what was for me a landmark visit. That is because I was born in the Veneto area and emigrated to Canada with my mother and brother in 1956, going through the great arrivals hall of Pier 21. We travelled in one of those 8-berth cabins you mention, taking turns to sleep in the single berth my father had been able to afford, when he sent for us to join him in Canada, where he had found work a year earlier. I was only less than 3 years old at the time, but I have vivid memories of the long boat trip, the horrible salty soup we were made to eat, my mother's constant seasickness, and the moment we approached the Pier where my elated mother pointed out a waving man to us, and shouted out "Ecco papà! Ecco papà", but I had no idea who this "papà" was as I couldn't recall having ever seen him. And I was somewhat afraid of him during the 24-hour train ride that then took us to Montreal and to the tenement apartment with the rats in the basement, which then became "home".