I Left My Heart in Newfoundland/Ho lasciato il mio cuore in Newfoundland

Wayne Johnston on writing home from afar/Wayne Johnston: scrivere della propria terra da lontano

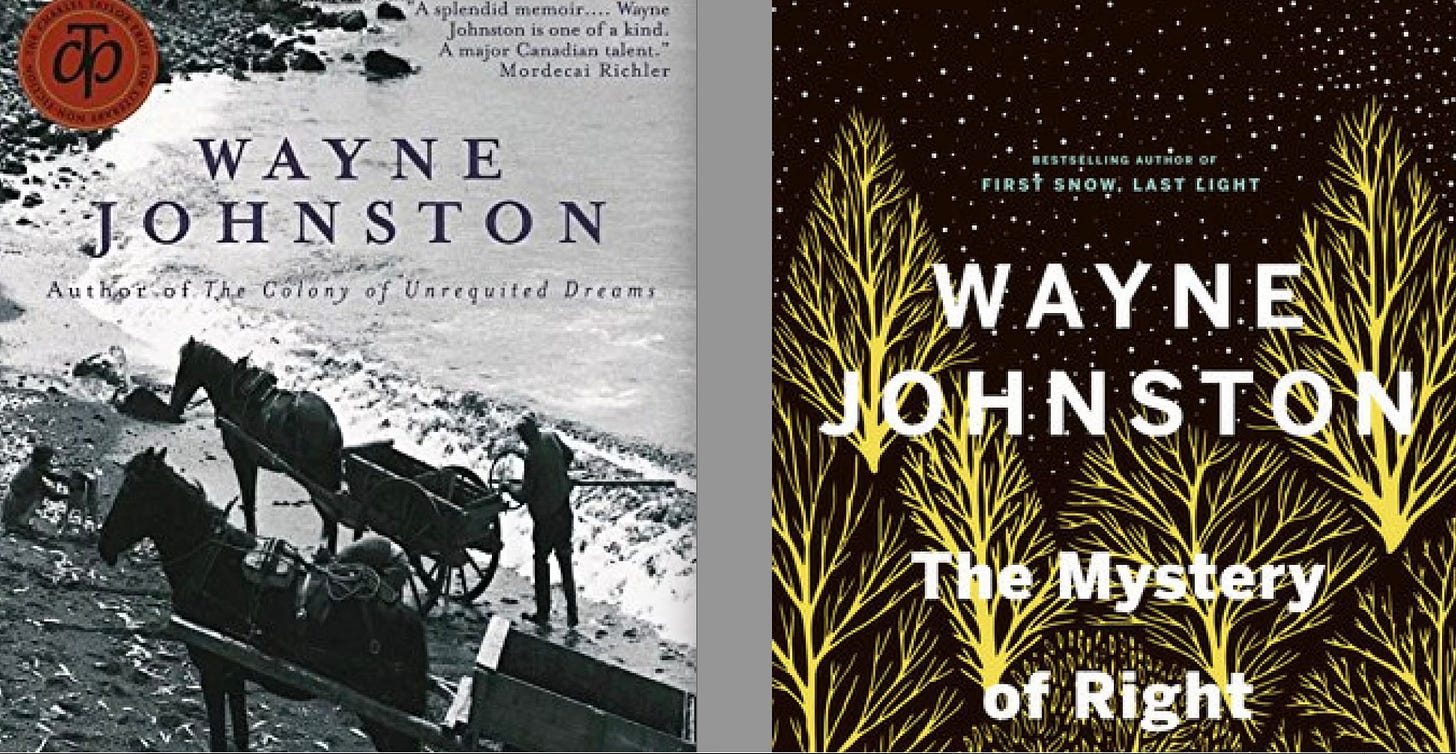

Having crossed the country from coast to coast, we’ve arrived in Newfoundland guided by the voice of one of its finest storytellers—Wayne Johnston, whose novels have long captured the spirit and complexity of this singular island. Born in Goulds, NL Johnston has earned national and international acclaim for books like The Colony of Unrequited Dreams—named by “The Globe and Mail” as one of the 100 most important Canadian books ever written—and The Divine Ryans, a comic satire of family life that won the 1991 Thomas Head Raddall Award and was adapted into a feature film in 1999, with Johnston penning the screenplay. His recent memoir, Jennie’s Boy, is a tender and humorous recollection of his childhood years—and has already made the Canada Reads 2025 longlist. Now based in Toronto, Johnston continues to captivate readers across the country with his rich storytelling, unmistakable voice, and deep-rooted connection to the island he still calls home—in spirit, if not in geography.

Question: Your novels often return to Newfoundland, its landscape, history, and people. What continues to draw you back to the island in your writing, even after many years living away from it?

Wayne: It’s a question whose answer eludes me. When you visit Newfoundland, you’ll understand why even for those who leave the island never truly lets them go. Newfoundlanders may move away, but they rarely put down roots elsewhere. They simply drop anchor for a while. Eventually, they haul it back up and return home—perhaps in the literal sense, or perhaps only in their minds or spirit. I think it has something to do with the nature of islands: how they seem to be self-contained worlds.

In that regard, my literary perspective has been shaped by West Indian writers. Derek Walcott’s essays, in particular, made me see islands differently. Still, the question of what Newfoundland literature should be has always haunted me. Should it follow the English tradition or embrace its unique cultural heritage? I try to write about Newfoundland in a way that aligns with the broader tradition of English literature—while remaining anti-colonial in my approach.

Question: What makes Newfoundland so special, in your opinion?

Wayne: It’s a combination of elements that makes it unique: its history as an independent nation, its remote location, and its striking natural beauty. The fact is, Newfoundlanders have a fierce love for their place, but the island doesn’t offer them the means for self-support, forcing them to leave. And they take that love of country with them, trying to keep it alive—even as they swallow their pride about needing to be part of a larger country in order to make a living. That’s the tension within every Newfoundlander’s heart: how do you keep your sense of nationality alive when you’re part of a larger country?

Newfoundlanders have an enormous envy of Iceland. They’ll never admit it, but they do—and for good reason. Iceland is an island with, what, 230,000 people? Yet it’s managed to thrive as an independent nation, largely because its fishery was protected early on—unlike ours. That protection allowed Iceland to preserve both its independence and its pristine culture. That hasn’t been the case for Newfoundland, whose history of colonization by the British sets it apart. Still, Newfoundlanders are deeply proud of their distinct heritage.

Question: And how do they maintain their distinct identity within Canada?

Wayne: They see themselves as Newfoundlanders first, and Canadians second. This is partly due to their history as an independent nation, and partly to their geographical isolation. Don’t get me wrong: most Newfoundlanders are patriotically Canadian, but there’s always a sense of being apart from the rest of the country.

This push-and-pull dynamic is central to how Newfoundlanders see themselves. They are proud of their heritage—its music, oral traditions, and dance, all deeply rooted in the past—yet they are also acutely aware of their economic limitations. And, I would say, they feel a sense of bitterness about not having full self-determination.

Question: That brings us to Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation in 1949. What were the main arguments in favor of joining Canada?

Wayne: At the time, you couldn’t make a romantic argument for joining Canada—most Newfoundlanders had never even been there. You couldn’t appeal, let’s say, to the majestic mountains of British Columbia—no one had seen them. In fact, most Newfoundlanders who had left had gone to the United States to live and work—and many never returned. So when Joey Smallwood campaigned for Confederation, he focused on the economic benefits it would bring to Newfoundland.

For instance, the baby bonus: many families in Newfoundland—especially Catholic ones—had up to 20 kids. Well, Smallwood said, every single child would bring in a certain amount of money. And in many ways, he was right. Outside the Avalon Peninsula, in the communities around the Bay, poverty was staggering. Tuberculosis, smallpox, and other diseases were widespread. As Premier Furey recently noted in his resignation speech, Newfoundland joined Canada for economic and pragmatic reasons—not out of love for Canada. He said, “We love Canada now.” I don’t even know if he meant it, but he said it. Back then, though, we knew nothing about Canada.

Question: Your father was against Confederation...

Wayne: He was definitely against it—he sided with Peter Cashin, the leader of the Anti-Confederates—and he never got over the defeat. He was also deeply affected by the way the events unfolded. My grandfather, who also opposed Confederation, died of a heart attack two days after the referendum. At the time, my father was studying in Nova Scotia and didn’t have the money to return for the funeral. So you have this man who, the next time he managed to come home, found himself in a different country—and without his father. Everything connected to the past was gone.

That sense of loss and change permeated our household. And since my mother was pro-Confederation, there were often unspoken tensions at the dinner table. These experiences deeply influenced my writing, particularly in Baltimore’s Mansion—a deeply personal book that explores my relationship with my father and his struggles with Newfoundland’s changing identity.

Question: How was your relationship with your father?

Wayne: We were quite close—we talked a lot, and I felt a deep connection with him. He wasn’t a strict father. What marked him most was his deep disillusionment with Newfoundland joining Canada. At the same time—paradoxically—he wanted to be a worldly success. But he didn’t want to leave Newfoundland, and that tension shaped his whole life. He came to see his unwillingness to leave as something that placed a kind of bell jar over how successful he could be.

He was always torn—on one hand, he felt limited by his attachment to Newfoundland; on the other hand, he loved it deeply. He lived among people who were trying hard to force themselves to become Canadian, because they felt they had to. He taught me to fish, and we shared a love for the ocean and the natural beauty of Newfoundland. Despite his inner struggles, he was a major influence on both my life and my writing.

Question: How has growing up in a close-knit community like Newfoundland influenced your writing?

Wayne: I think Newfoundlanders, influenced as they are by Irish culture, incorporate humour and irony into their writing more than other Canadians. It’s a way of using language to push back and cope with being the underdog. Like Indigenous peoples and Quebecers, Newfoundlanders use satire and mockery as a means of survival. Humour becomes a way to release pressure and find joy even in difficult situations. My writing reflects this Newfoundland tradition—using humour to navigate life’s challenges.

Question: Humour as a cathartic element?

Wayne: Absolutely. Humour is a way of fighting back verbally and expressing dissatisfaction. Ray Guy, a satirical columnist, was a genius at this. He wrote a column every day for 21 years during Joey Smallwood's reign, each one hilariously funny and devastatingly satirical. When I created the character Sheila Fielding [protagonist of The Colony of Unrequited Dreams], I had Ray Guy in mind, though I was nearly lynched for saying so because people thought I was equating a male figure with a female character. In fact, it was more about capturing the spirit of his writing.

Question: How has moving away from Newfoundland played a role in your writing?

I don’t idealize Newfoundland, you know. There are definite downsides to island life and living in a remote place. At a certain point, I felt the need to get away from that sense of parochialism—that small-world provincialism that can start to feel stifling. I began asking myself: do I need to live in Newfoundland to write, or do I actually need to be away from Newfoundland to write? The more I thought about it, the more I realized I needed distance—even setting aside everything that led to The Mystery of Right and Wrong. That whole experience—when my brother-in-law and I discovered that our wives, two sisters and daughters of a white South African who had migrated to Newfoundland, had been abused by their father—was overwhelming.

Being surrounded every day by the very people and community I was writing about—it was just too much. Too intense. I couldn’t gain the kind of emotional or imaginative perspective I needed. So I left. At first, I considered going back to New Brunswick, where I’d spent time before. But that wasn’t far enough. Nova Scotia wasn’t far enough either. Prince Edward Island—not far enough. I even briefly thought about the United States, but that never really felt right. In the end, I told myself: if you’re a Newfoundlander and you’re not going to live in Newfoundland, but you still want to stay in Canada, you may as well go where other Newfoundlanders go. And that usually means Alberta, or Ontario.

I chose Toronto. Living here has allowed me to separate my personal life from my creative and historical concerns. It’s given me the space to see Newfoundland from a distance—geographically, emotionally, intellectually. That distance has been crucial to my writing. It has allowed me to examine things with a clearer eye, and added a layer of reflection and complexity to my work that I couldn’t access while still living on the island. Sometimes, to write honestly about a place, you have to step away from it.

Ho lasciato il mio cuore in Newfoundland

Domanda: Nei suoi romanzi il Newfoundland è una presenza quasi costante: con i suoi paesaggi, la sua storia, la sua gente. Cosa la spinge a tornare sull’isola, almeno nella scrittura, dopo tanti anni che non vive più lì?

Wayne: È una domanda cui non riesco mai a trovare una risposta soddisfacente. Ma quando arriverete là, capirete perché anche chi se ne va non se ne va mai del tutto. I Newfoundlander possono anche andarsene a vivere altrove, ma raramente vi mettono radici: diciamo che vi gettano l’ancora per un po’. E, prima o poi, la tirano su e tornano indietro – chi in senso letterale, chi solo con la testa o con l’anima. Credo che c’entri il fatto che le isole sono mondi per certi versi a sé stanti, auto-referenziali.

In questo senso, mi sento vicino a certi scrittori caraibici: sono stati loro, soprattutto alcuni saggi di Derek Walcott, a farmi vedere le isole con occhi diversi. Poi c’è la questione – per me mai risolta – di cosa debba essere davvero la letteratura del Newfoundland. Deve ricalcare il modello inglese? O deve rivendicare la propria specificità culturale? Io cerco di percorrere la via di mezzo: racconto la mia terra restando dentro la grande tradizione letteraria inglese, ma con uno sguardo profondamente anti-coloniale.

Domanda: Cosa rende speciale il Newfoundland?

Wayne: È l’insieme di più elementi che lo rende unico: la sua storia di nazione indipendente, l’isolamento geografico, e una natura di una bellezza stupefacente. I Newfoundlander hanno un amore viscerale per la loro terra, ma è un amore complicato: l’isola non offre loro quanto serve per permettere loro di restare e mantenersi economicamente. Quindi sono costretti ad andarsene. Ma quell’amore se lo portano dietro, e cercano di tenerlo vivo anche se devono mettere da parte il loro orgoglio e accettare di far parte di un altro paese, più grande, per poter avere un futuro. È questa la realtà con cui si confrontano: come fai a restare te stesso, a sentirti ancora “nazione”, quando ormai sei solo una provincia tra tante?

C’è una cosa che i Newfoundlander non ammetteranno mai, ma che è assai indicativa: hanno grande invidia per l’Islanda. Il motivo è assai semplice. L’Islanda è un’isola, con una popolazione di circa duecentotrentamila persone, eppure è riuscita a farcela come nazione. In gran parte grazie alla pesca, che hanno saputo proteggere fin dall’inizio, cosa che da noi non è successa. Il che ha permesso loro di conservare l’indipendenza e anche una cultura intatta. In Newfoundland le cose sono andate diversamente e il retaggio coloniale britannico ha lasciato un segno deciso. Ma il senso di appartenenza è fortissimo, e i Newfoundlander restano profondamente orgogliosi della propria identità.

Domanda: E come riescono a mantenere questa identità distinta all’interno del Canada?

Wayne: I miei compatrioti si sentono prima di tutto Newfoundlander, e solo dopo canadesi. In parte è per via della loro storia di nazione autonoma, in parte per l’isolamento geografico che caratterizza l’isola. Non fraintendetemi: la maggior parte di loro è patriotticamente canadese, ma resta pur sempre una distanza nell’auto-percezione, un senso di separazione dal resto del paese.

Questa tensione tra attrazione e distacco è al cuore dell’identità dei Newfoundlander. Sono fieri della loro cultura—della musica, delle tradizioni orali, della danza—tutte espressioni profondamente radicate in un passato ancora molto vivo. Ma, al tempo stesso, sono pienamente consapevoli dei limiti economici che li condizionano. E, direi, provano una certa amarezza per non aver mai avuto una piena autodeterminazione.

Domanda: Stiamo arrivando, immagino, alla questione dell’adesione alla Confederazione nel 1949. Quali furono i principali argomenti a favore dell’unione con il Canada?

Wayne: All’epoca non aveva molto senso cercare di fare un discorso ispirato, romantico, sull’ingresso nel Canada—la verità è che quasi nessun Newfoundlander ci era mai stato. Non potevi evocare, che so, le maestose montagne della Columbia Britannica: nessuno le aveva mai viste. Anzi, quelli che erano emigrati, nella maggior parte dei casi erano finiti negli Stati Uniti, per lavorare–e molti non erano più tornati. Per questo Joey Smallwood [leader della campagna pro-Confederazione nel referendum del 1948, e poi primo Premier del Newfoundland come provincia canadese], puntò tutto sul piano economico.

Parlava, per esempio, del “baby bonus”: molte famiglie cattoliche avevano anche venti figli, e lui diceva—con ogni bambino, arriva un assegno. In fin dei conti, aveva ragione. Fuori dalla penisola di Avalon [quella in cui si trova la capitale St. John’s], nei villaggi intorno alla baia, la povertà era a livelli indicibili. Malattie come la tubercolosi e il vaiolo erano ancora molto diffuse. Come ha detto di recente il premier Furey nel suo discorso di dimissioni, Newfoundland è entrata in Canada per ragioni economiche e pratiche, non per un sentimento d’amore. E ha aggiunto, “Oggi amiamo il Canada”; non so neanche se lo pensasse davvero, ma l’ha detto. All’epoca, però, del Canada non sapevamo quasi nulla.

Question: Suo padre era contro l’adesione al Canada...

Wayne: Si, era assolutamente contrario—era dalla parte di Peter Cashin, il leader del movimento anti-adesione—e non ha mai davvero superato quella sconfitta. Anche perché restò profondamente segnato da come si svolsero gli eventi in quel periodo. Mio nonno, anche lui contrario alla Confederazione, morì d’infarto due giorni dopo il referendum. Mio padre, che in quel periodo studiava in Nova Scotia, non aveva nemmeno i soldi per tornare a casa per il funerale. Quindi immaginatevi quest’uomo che, quando finalmente riesce a tornare sull’isola, si trova in un altro paese—e per giunta senza più suo padre. Tutto ciò che rappresentava il suo passato era sparito.

Quella sensazione di perdita, di rottura, ha segnato profondamente l’atmosfera in cui sono cresciuto. Anche perché mia madre era invece a favore della Confederazione—quindi a tavola, anche se nessuno ne parlava apertamente, le tensioni c’erano eccome.

Tutte queste emozioni e sensazioni sono in un modo o nell’altro finite nei miei libri, soprattutto in Baltimore's Mansion, forse il più personale di tutti, quello in cui ho cercato di esplorare il rapporto con mio padre e il modo in cui ha vissuto, sulla propria pelle, il cambiamento d’identità del Newfoundland.

Domanda: Che rapporto aveva con suo padre?

Wayne: Eravamo molto legati—parlavamo tanto, e ci capivamo davvero. Non era un padre severo. La cosa che ha maggiormente segnato la sua vita è stata la profonda delusione per l’unione con il Canada. Eppure, paradossalmente, coltivava l’ambizione di affermarsi nel mondo. Ma non voleva andarsene dal Newfoundland, e questa contraddizione ha attraversato tutta la sua esistenza. Col tempo arrivò a vedere quel suo restare come una gabbia di vetro che limitava quello che avrebbe potuto diventare.

Era costantemente lacerato: da un lato sentiva che il legame con la sua terra lo frenava, dall’altro la amava visceralmente. Ha vissuto circondato da persone che cercavano in tutti i modi di convincersi di essere canadesi, perché pensavano che fosse necessario farlo. Mi ha insegnato a pescare, e insieme abbiamo condiviso l’amore per il mare e per le bellezze naturali della nostra isola. Nonostante i suoi conflitti interiori, è stato una figura fondamentale nella mia vita—e nella mia scrittura.

Domanda: In che modo crescere in una comunità come quella del Newfoundland ha influenzato la sua scrittura?

Wayne: Credo che i Newfoundlander, che sono assai vicini alla cultura irlandese, mettano nella loro scrittura più umorismo e ironia rispetto ad altri scrittori canadesi. È un modo di far diventare il linguaggio una forma di resistenza, un modo per affrontare la propria condizione di “underdog”. Come d’altronde fanno anche le First Nation e i Quebechesi, usano la satira e il sarcasmo come misure di sopravvivenza. L’umorismo diventa uno strumento per scaricare le tensioni cui sei costantemente sottoposto e trovare un po’ di leggerezza, anche nei momenti difficili. Ecco, la mia scrittura riprende questa tradizione molto presente nel Newfoundland: usare l’umorismo come antidoto alle sfide che la vita ti propone.

Domanda: L’umorismo come elemento catartico?

Wayne: Assolutamente sì. L’umorismo come modo per esprimere il proprio malcontento. Ray Guy, un giornalista satirico, in questo era geniale. Ha scritto una rubrica ogni giorno per 21 anni, durante il governo di Joey Smallwood, e ogni pezzo era sia esilarante che devastante nella sua verve satirica. Quando ho creato il personaggio di Sheila Fielding [protagonista del romanzo The Colony of Unrequited Dreams], avevo in mente proprio Ray Guy, anche se quando l’ho detto mi hanno quasi linciato perché la gente qui pensava che stessi mettendo sullo stesso piano un uomo e un personaggio femminile. In realtà, cercavo di restituire lo spirito del suo stile.

Domanda: In che modo allontanarsi dal Newfoundland ha influenzato la sua scrittura?

Wayne: Non è mia intenzione idealizzare questa terra. La vita su un’isola e in un luogo così isolato ha sicuramente aspetti negativi. Tanto che, a un certo punto, ho sentito il bisogno di allontanarmi da quel senso di provincialismo ristretto, quella mentalità da piccolo mondo che può diventare soffocante. Ho cominciato a chiedermi: per scrivere ho bisogno di vivere nel Newfoundland, o al contrario ho bisogno di star lontano dal Newfoundland? Più ci pensavo, e più capivo che avevo bisogno di distanza; e questo anche senza considerare tutto quello che ha portato alla scrittura autobiografica di The Mystery of Right and Wrong. Quell’esperienza, quando mio cognato ed io abbiamo scoperto che le nostre mogli, due sorelle figlie di un sudafricano bianco emigrato nel Newfoundland, erano state vittime di abusi da parte del padre, è stata devastante.

L'essere ogni giorno circondato dalle stesse persone e dalla comunità di cui scrivevo era diventato troppo. Intenso fuori misura. Non riuscivo a trovare la prospettiva emotiva o immaginativa di cui avevo bisogno. Quindi me ne sono andato. All’inizio avevo pensato di tornare in New Brunswick, dove avevo già vissuto, ma non era sufficientemente lontano. Nemmeno la Nova Scotia lo era. E neppure Prince Edward Island. Ad un certo punto presi anche in considerazione gli Stati Uniti, ma non mi è mai davvero sembrata un’ipotesi convincente. Alla fine mi sono detto: se sei un Newfoundlander e non vuoi vivere nella tua terra, ma vuoi restare in Canada, allora tanto vale andare dove vanno gli altri Newfoundlander. Di solito questo significa Alberta o Ontario.

Ho scelto Toronto. Vivere qui mi ha permesso di separare la mia vita personale dalla dimensione creativa e storica della mia scrittura. Mi ha dato lo spazio per guardare al Newfoundland da lontano, sia sul piano geografico che su quello emotivo e intellettuale. Quella distanza è stata fondamentale per la mia scrittura. Mi ha consentito di osservare le cose con maggiore lucidità, aggiungendo ai miei testi un livello di riflessione e complessità che, finché vivevo sull’isola, non riuscivo a raggiungere. A volte, per riuscire a scrivere in modo autentico di un luogo, bisogna prima allontanarsene, sia fisicamente che interiormente.

Great interview, highlighting the dilemma of island life. As an aside, the real reason to make Newfoundland Canadian was geopolitical. After WWII, Britain did not want responsibility for Newfoundland any longer, but for strategic reasons allowing it to be an independent country was unthinkable. The US did not want it, so Canada was given the job of coaxing Newfoundland from its (ungovernable) Dominion status to become part of Canada. It worked, barely.

Interesting to read. I will purchase his books. Thank you.