Let’s Not Give Up on our Canada/Non rinunciamo al nostro Canada

A conversation with Michael Springate/Una conversazione con Michael Springate (il testo in italiano segue quello in inglese)

Character-driven narratives, belonging, resistance and why it is worth holding on to “this” Canada/Narrazioni incentrate sui personaggi, senso di appartenenza, resistenza e perché vale la pena tenersi “questo” Canada

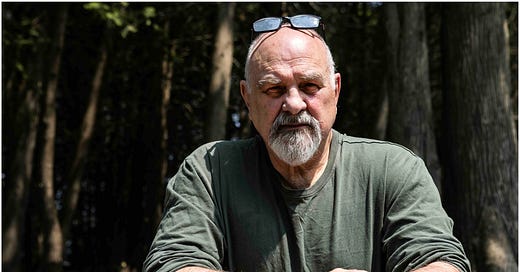

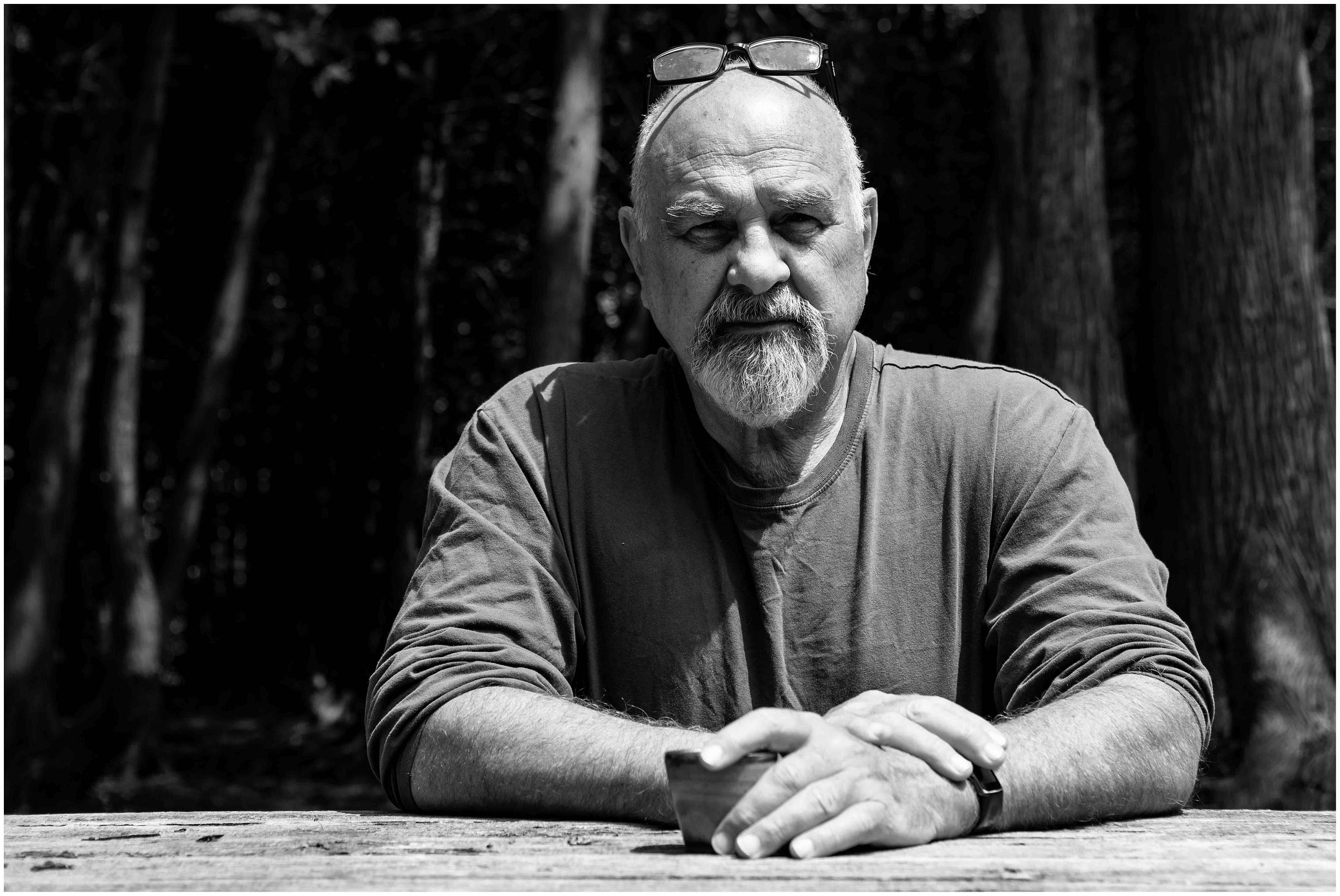

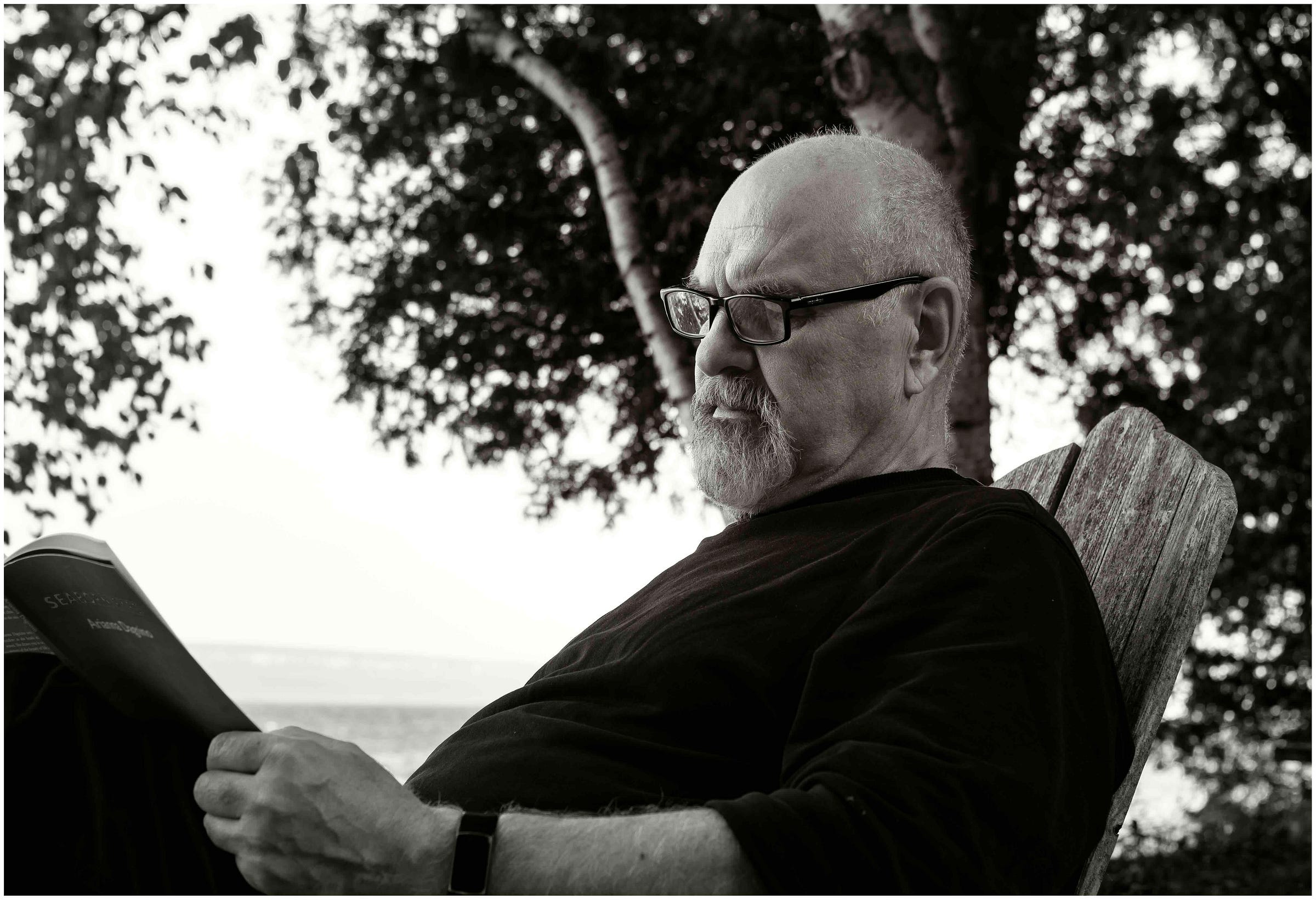

A Canadian literary force, Michael Springate is celebrated for his sharp, politically charged fiction. His notable works include the novel The Beautiful West & The Beloved of God and its gripping sequel Allegiance. With a canvas that spans from university lecture halls in Montreal to stark detention centres in Egypt, from the ancient catacombs of Kom el-Shoqafa to the vibrant dance floors of modern Greece, Springate threads a meditation on justice, cultural memory, and the fragile bonds that define our commitments in today's interconnected world.

We met Michael at his cottage by Colpoy’s Bay (South Bruce Peninsula), on the waters of Lake Huron, Ontario.

Q.: Your work often weaves together personal narratives and political themes. What draws you to explore politics through fiction rather than, for example, an essay or a journalistic piece?

Springate: I’d say that my work explores the relationships between people. I'm character-oriented, and that has led to fiction. There is no intent of an objective reality. In fact, it is many subjective realities that are put into context. The word politics means different things to different people, but to me, politics is just another framework for a series of relationships between people. We have developed vocabularies to talk about the nature of those relationships, including a political vocabulary, a vocabulary of historical movements, a vocabulary of ideologies, and a vocabulary of collective interests. I actually like the fact that our culture carries a range of different vocabularies. We approach a greater understanding of the complexity of our lives by understanding people and how they see things.

My thinking doesn't try to transcend the characters that I'm writing for. It rather tries to get the characters right and understand the vocabularies that those characters use. One thing that surprises me a lot in contemporary literature is that we don't allow the fullness of vocabularies that contemporary people actually use.

People are far from stupid, they are quite insightful and intelligent and often educated, whether officially or not. It's in the nature of the human to be curious, to engage, to develop configurations of thought. That’s what interests me.

Q.: When incorporating political elements into your narratives, how do you maintain a balance between storytelling integrity and political engagement—especially when you hold a personal political perspective?

Springate: I work hard. It's work. It's focusing on that issue. It's research. I write so that I can research and I research so that I can write. The two things are linked; in the writing there has to be a joy of discovery. Well, you try to keep alive the joy of discovery. If you just follow a pre-set ideological framework that you like or you believe your character likes, there's very little joy of discovery.

As a writer, I want to feel I'm learning constantly, and that the characters are surprising me, which they do, and that I am surprised by the nature of the world, which I am. But let me add a shading here: we use the word politics, but I’d use the word history. People have often sophisticated understandings of history and we should allow that sophistication into our conversations, because they affect our relationships. The quality of life that we lead or live is mostly determined by the quality and nature of the relationship that we're in, not the correctness of our political thought or historical thought.

But it's very hard to talk about the nature of the relationships that we're in without referring to either political movements, political thoughts, or historical trends, or historical understandings.

Q.: So, you would you allow your characters to think differently, if not the opposite of what you might be inclined to...

Springate: Yes. Someone with whom I could argue? Absolutely. And thus I choose a character with whom I do not agree, and give them – or assume that they have – integrity, which they probably do. There may be limits to that integrity, just like there are limits to my own integrity. And they probably have a different way of arguing, too. Some of the most interesting scenes are when one character believes that they're arguing according to certain rules and the other character, in fact, is arguing in a completely different context with a different set of references. And to me that often happens in real life, so to speak, and I'm fascinated by that.

Q.: A lot of your writing touches on displacement, identity, and institutional structures. Do you also see fiction as a place of resistance?

Springate: The short answer is yes. In my collection "Revolt Compassion," all six works are definitely about resistance. But resistance to what exactly? I prefer to use the word “reformulation.” We should allow ourselves to reformulate, to reconsider, to begin again. Resistance and beginning again are tightly linked. You have to have the courage to begin again. I'm a bit wary of the romanticization of the word resistance, which has swept America. Everybody's all of a sudden in the resistance. I prefer to say that I think everybody's engaged in reformulation...

People are trying to rethink the world because, in fact, they find that their conceptual apparatus is not up to the burden. They no longer feel they understand the world in which they find themselves in real terms. Very few are in an active resistance but many are in an active reformulation, which is related to their capacity to resist or to demand or accept change. So, we live in a time that somewhat romanticizes alienation. We have been romanticizing alienation for a very long time. This is tightly tied to the idea of belonging. Alienation and belonging are kind of flip sides of the same coin.

I don't particularly want to highlight either the alienation or the sense of belonging. I want to make them both active in the lives of my characters. Sometimes they feel like they belong and sometimes they feel alienated. This will cause different actions that will cause different decisions to be made. You should be able to see that in the narrative. In fact, the narrative evolves from both–being rebuffed and being accepted.

Q.: Speaking of belonging: Canada is facing pressures both from internal divisions, and from global trends. What concerns or hopes do you see for the future of Canadian democracy and cultural identity?

Springate: That's a big one. Yes, it's a big one [Long pause]. The words that immediately crop up are capitalism, colonialism, and the cooperative movement. I’ll start from this one. The Wheat Board [CWB] was a very important Canadian step. It was a cooperative agreement among the farmers on the prairies to work together and sell their produce on a global basis through the CCF [Co-operative Commonwealth Federation]. It no longer exists as it was sold off to major capitalist interests. We have a supply-side management structure for eggs and dairy, which has allowed us to have a healthy farming industry, healthy products that aren't as drug-laden as the American dairy and eggs and meat. That structure is now under stress. Every time a trade arrangement or agreement is made, there’s an attempt to dismantle that way of Canadians cooperating together.

Two major Canadian financial institutions, Caisse Desjardins in Quebec and Vancity in Vancouver, are a trust co-op, not a bank in the pure sense. Caisse Desjardins works throughout all small communities in Quebec and invests differently than banks, and has a different relationship to its clientele. What I'm saying is that there are ways for citizens working together and cooperating, according to different dynamics and different moments. And that ultimately is what's going to hold them together. If for instance we allow private equity in the health field to come in with their investments, we privatize medical assistance. And why would we privatize medical assistance? Well, because for some people it's a guaranteed flow of money. The government pays out billions for healthcare. That flow of billions of dollars becomes a target for private equity funds who want a portion of it. We need to strike a balance between different economic needs, allowing private investment only if it’s useful and doesn’t become destructive. We’re living in a time where the middle class has been played out and has less resources than before, but the question remains: do we cannibalize ourselves even more, or do we rebuild the structures through which we can resist the unfettered capitalism that has led us to a kind of cannibalism?

Q.: As for the talk about Canada being the 51st state or annexed by the United States?

It's not like that somebody woke up one morning and said, hey, this would be a good idea. There are major industries who believe that’s a great idea. The oil and gas industry is one, because in the United States there are much fewer restrictions than in Canada. The same happens with the health industries: there's an incredible push to privatize medicine and the medical health systems. We used to have our own pharmaceutical industry and we sold it off. I mean, throughout many parts of our economy, there's immense pressure to change the nature of our cooperative agreements to make it easier for capital to make a profit in Canada. And that’s going to be a real challenge.

Q.: So, how should Canadians resist or–as you put it–reformulate all this?

Springate: Well, do we really want to give up all sorts of cooperative arrangements so that the American investment class can make more money? Do we want to give up traditions of cooperative institution-making so that American equity funds can grow and make profits in the short term? No, we don’t want to do that. We’ll have to deal with the current stage of capitalism. We’ll have to sort out how people can actually cooperate, what structures of cooperation we have need to be maintained and even strengthened.

Then colonialism. That Canada was where French and British colonialism came to a showdown is a good thing for us. We have to understand and deal with the effects of our colonialism on Indigenous people. And if we can keep that conversation alive, we will also have the tools to counter American colonial interests. An astute evaluation of the nature of capitalism is important for Canada. An astute evaluation of the nature of colonialism is important for Canada. An astute evaluation of the cooperative ventures that Canadians have succeeded with so powerfully in the past is a critical component of the future of Canada.

And we need to maintain free and good education and medical support, and appropriate policies of redistribution, which is always a contentious issue. And we need to be open to a recognition of languages, not just French and English, but Aboriginal languages, and other major ones. I think it's actually very important for our future that we be open to more than one official language. We now have two and we should maintain that commitment; in certain jurisdictions we have more than two and we need to maintain that commitment. Why? In the great scheme of things, we're not necessarily affecting a lot through that but we're stating that various communities have the right to interpret the world the way they wish. That we are not going to interpret the world only through an Anglo-American tradition. That our country is a country that refuses to see the world only through one cultural lens. I think that's a strength and that our educational sector must maintain that among the youth. I welcome the increased use of different languages and I don't actually think it's a problem because the lingua franca is so powerful that it'll always be there; but we need to understand that one linguistic enterprise, however successful it may be, cannot actually represent the wholeness of our world. We're lucky to be a large immigrant society and it would be a good thing if we can keep alive what we learnt from that.

I don't know if Canada can survive, but every time it gets close to not surviving, there is a kind of awakening, and people say, well, hold on a minute, do I really want to give this up? Is it really worthwhile not to have a Canada?

Non rinunciamo al Nostro Canada

Figura di spicco nel panorama letterario canadese, Michael Springate è noto per la forza narrativa e l’intensità politica dei suoi romanzi. Tra le sue opere più rilevanti si segnalano The Beautiful West & The Beloved of God e il suo avvincente seguito Allegiance. Con una narrazione che si muove tra le aule universitarie di Montréal e i centri di detenzione in Egitto, tra gli antichi cunicoli di Kom el-Shoqafa e le piste da ballo della Grecia contemporanea, Springate costruisce una riflessione profonda sulla giustizia, la memoria culturale e i legami – spesso fragili – che definiscono le nostre scelte e appartenenze in un mondo sempre più interconnesso.

Abbiamo incontrato Michael nel suo cottage di Copoy Bay, sulle acque del Lake Huron.

D.: Il tuo lavoro intreccia spesso narrazioni personali e tematiche politiche. Cosa ti spinge a esplorare la politica attraverso la finzione, invece che con un saggio o un articolo giornalistico?

Springate: Il mio lavoro vuole esplorare i rapporti tra le persone. Per questo si incentra su personaggi che si muovono in un mondo che creo narrativamente. Non cerco una realtà oggettiva. Al contrario, cerco di mettere in relazione una molteplicità di realtà soggettive. “Politica” è una parola che ha significati diversi per persone diverse, ma per me rappresenta solo un altro contesto relazionale. Abbiamo sviluppato vocabolari per parlare della natura di questi rapporti: un vocabolario politico, uno storico, uno ideologico, uno legato agli interessi collettivi. Il fatto che la nostra cultura abbia una gamma così ampia di linguaggi è una cosa estremamente positiva. Se vogliamo provare ad afferrare la complessità della vita dobbiamo comprendere le persone e il loro modo di percepire le cose.

Il mio pensiero non intende imporsi sui personaggi per cui e con cui scrivo: cerco piuttosto di capirli, anche attraverso il registro espressivo che usano. Ecco perché trovo sorprendente che la letteratura contemporanea spesso non dia conto della pienezza espressiva di cui le persone reali fanno uso quotidiano.

Le persone non sono stupide: sono spesso acute, intelligenti e, direi, colte, formalmente o informalmente. È nella natura umana essere curiosi, mettersi in gioco, costruire schemi di pensiero. È questo che mi interessa.

D.: Quando inserisci elementi politici nei tuoi romanzi, come mantieni l’equilibrio tra integrità narrativa e impegno politico—soprattutto se hai una tua visione personale su quegli argomenti?

Springate: Lavoro. Lavoro duro. È questo l’equilibrio: impegno, concentrazione, ricerca. Scrivo per poter fare ricerca e faccio ricerca per poter scrivere. Le due cose si nutrono a vicenda. La scrittura deve dare la gioia della scoperta. Se ti limiti a seguire un’impostazione ideologica prestabilita, tua o che fai condividere ai tuoi personaggi, quella gioia svanisce.

Cerco di restare aperto all’apprendimento, voglio che i personaggi mi sorprendano—e lo fanno—e voglio sorprendermi del mondo—e mi capita spesso. Ma lasciami aggiungere una sfumatura: laddove si usa il termine “politica”, io preferisco parlare di “storia”. E le persone hanno spesso una comprensione articolata della storia e dovremmo far sì che quella lucidità entri nelle nostre conversazioni. La qualità della nostra vita è determinata, più che dal rigore del nostro pensiero politico o storico, dalla qualità delle relazioni in cui siamo immersi. Ma è difficile parlare della natura di tali relazioni se non si prendono a riferimento movimenti politici, idee storiche o tendenze ideologiche.

D.: Quindi permetti ai tuoi personaggi di pensare in modo diverso, se non addirittura opposto, rispetto al tuo?

Springate: Certamente. Un personaggio con cui potrei litigare? Senza dubbio. Per questo ne scelgo sempre uno con un punto di vista distante dal mio, riconoscendogli — o immaginando che abbia — una sua integrità. Che, con ogni probabilità, è reale. Un’integrità forse non assoluta, certo, ma neppure la mia lo è. Spesso, non sono solo le idee ad essere diverse, ma anche come le si argomenta. Le scene più intriganti emergono proprio quando un personaggio conduce la discussione su certe basi, mentre l’altro lo fa con un set di riferimenti completamente diverso. Peraltro, è ciò che capita continuamente anche nella vita reale, ed è qualcosa che mi affascina.

D.: Molti tuoi scritti toccano temi come lo spaesamento, l’identità, le strutture istituzionali. Vedi la narrativa anche come un luogo di resistenza?

Springate: La risposta breve è sì. Tutti i sei contributi raccolti in Revolt Compassion trattano in un modo o nell’altro il tema della resistenza. Ma resistenza a cosa, esattamente? Anche qui preferisco un altro termine: “riformulazione”. Dovremmo concederci il diritto di riformulare, ripensare, ricominciare. Resistere e ricominciare sono concetti strettamente legati. Serve coraggio per ricominciare. Ho una certa diffidenza nei confronti della retorica romantica con cui ora in America si parla di “resistenza”: oggi tutti sembrano appartenere a una qualche forma di resistenza. Io credo che in realtà la maggior parte delle persone stia riformulando.

Stanno cercando di ripensare il mondo perché sentono che gli strumenti concettuali che hanno non bastano più. Non capiscono più, nei fatti, il mondo in cui si trovano. Pochi praticano resistenza attiva, molti ‘riformulano’. E questa capacità di riformulazione è strettamente legata alla capacità di resistere, di chiedere o accettare il cambiamento. Viviamo in un’epoca che tende a romanticizzare l’alienazione. E lo facciamo da tempo.

Ma alienazione e appartenenza sono due facce della stessa medaglia. Non è mia intenzione enfatizzare l’una o l’altra. Ma voglio che entrambe permeino la vita dei miei personaggi. Che a volte si percepiscono come parte di qualcosa, e a volte si sentono alienati dal contesto sociale. Il che li spinge ad agire in modi diversi, a prendere decisioni diverse. È da qui che nasce la narrazione.

D.: A proposito di appartenenza: il Canada oggi è sotto pressione, sia per divisioni interne, che per effetto delle tendenze globali. Che preoccupazioni o speranze hai per il futuro della democrazia e dell’identità culturale canadese?

Springate: È una domanda enorme [si prende del tempo prima di rispondere]. Le prime parole che mi vengono in mente sono: capitalismo, colonialismo e cooperazione. Parto da quest’ultima. Il Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) fu un’importante conquista: un accordo cooperativo tra gli agricoltori delle Prairies per vendere insieme i propri prodotti sul mercato internazionale tramite la CCF (Co-operative Commonwealth Federation). Oggi questa istituzione non esiste più e il mercato è in mano ai grandi interessi capitalistici. C’è ancora una struttura di gestione dell’offerta per uova e latticini grazie alla quale abbiamo un’industria agricola sana, e prodotti meno carichi di ormoni e farmaci di quelli americani. Ma quella struttura è oggi sotto attacco. Ogni volta che si stipula un accordo o un’intesa commerciale, si assiste a un tentativo di smantellare quel modo tutto canadese di cooperazione collettiva.

Due istituzioni finanziarie canadesi—Caisse Desjardins in Québec e Vancity a Vancouver—sono cooperative di credito, non banche tradizionali. Hanno un rapporto con i loro clienti diverso da quello tipico delle banche. Dico questo per evidenziare che esistono ancora modalità alternative, cooperative, grazie alle quali i cittadini possono collaborare e agire insieme, seguendo dinamiche diverse in momenti diversi. Ed è questo, in definitiva, ciò che li può tener uniti.

Ma se, ad esempio, permettiamo ai fondi di private equity di entrare nel settore sanitario con i loro investimenti, finiamo per privatizzare l’assistenza medica. Che è esattamente quello che alcuni vogliono perché è un flusso di denaro garantito. Lo Stato spende miliardi per la sanità e i fondi di private equity mirano ad accaparrarsene una parte.

Dobbiamo trovare un sano equilibrio: permettere l’investimento privato solo se utile e non diventa distruttivo. Viviamo in un’epoca in cui la classe media è stata marginalizzata e ha meno risorse di quanto avesse in passato, ma la domanda cruciale resta: ci cannibalizziamo ulteriormente o ricostruiamo quelle strutture che ci avevano permesso di tenere a bada un capitalismo sfrenato?

D.: E per quanto riguarda il discorso sul Canada come 51º stato o annesso agli Stati Uniti?

Non è che qualcuno si sia svegliato un mattino pensando che fosse una buona idea. Ci sono grandi settori industriali che ritengono che sia un’ottima idea. L’industria del petrolio e del gas, ad esempio, perché negli Stati Uniti ci sono molte meno restrizioni rispetto al Canada. Lo stesso vale per la sanità: c’è una forte spinta alla privatizzazione. Avevamo un’industria farmaceutica nazionale, l’abbiamo venduta. Sono molti gli ambiti della nostra economia in cui c’è una forte spinta a rivedere gli accordi di cooperazione, per facilitare l’ingresso e i guadagni del capitale in Canada. E su questo si giocherà una sfida importante.

D.: Quindi i canadesi come dovrebbero opporsi? O, come diresti tu, come dovrebbero riformulare la questione?

Springate: Cominciamo con il chiederci: vogliamo davvero smantellare tutte le strutture cooperative per far arricchire il capitale americano? Vogliamo sacrificare le nostre istituzioni cooperative per i profitti a breve termine di fondi di investimento stranieri? La risposta è no. Dobbiamo affrontare la fase attuale del capitalismo e capire come possiamo ancora cooperare. Dobbiamo mantenere e rafforzare le strutture di cooperazione esistenti.

Quanto al colonialismo: il Canada è stato il punto d’incontro e di scontro tra colonialismi francese e britannico, e questo può essere una forza. Dobbiamo comprendere e affrontare gli effetti del nostro colonialismo sulle popolazioni indigene. Se terremo viva questa conversazione, avremo anche gli strumenti per contrastare gli interessi coloniali americani. Fare una valutazione lucida della natura del capitalismo è importante per il Canada, come lo è fare una valutazione lucida della natura del colonialismo. E una valutazione altrettanto lucida delle imprese cooperative che i canadesi hanno saputo costruire in passato è un elemento fondamentale per il futuro del Paese.

Dobbiamo anche mantenere un’istruzione gratuita e di qualità, un sistema sanitario accessibile, e politiche adeguate di redistribuzione — un tema sempre delicato. E dobbiamo essere aperti al riconoscimento delle lingue, non solo del francese e dell’inglese, ma anche delle lingue aborigene e di altre lingue presenti nel Paese. È importante, per il nostro futuro, restare aperti all’idea di aver più di una lingua ufficiale. Attualmente ne abbiamo due, in alcune giurisdizioni anche più di due, ed è essenziale mantenere quest’impegno. Perché, in fin dei conti, non si tratta tanto di incidere su larga scala in materia di lingue parlate, quanto di affermare un principio: che le comunità hanno il diritto di interpretare il mondo secondo la propria prospettiva. Che il nostro è un Paese che rifiuta di vedere il mondo con un’unica chiave culturale, quella anglo-americana. Penso che questa sia una forza che il nostro sistema educativo deve trasmettere alle nuove generazioni. Vedo con favore l’uso di varie lingue e non credo possa costituire un problema: la lingua franca è talmente forte che continuerà comunque a esistere. Ma dobbiamo capire che un solo sistema linguistico, per quanto potente, non può rappresentare l’interezza del nostro mondo. Siamo fortunati a essere una società con una forte componente migrante, e sarebbe un bene se riuscissimo a conservare ciò che abbiamo imparato da questa esperienza.

Io non so se il Canada sopravviverà. Ma ogni volta che ci si avvicina al punto di non ritorno, c’è una sorta di risveglio, e le persone si chiedono: davvero vogliamo rinunciare a tutto questo? Vale davvero la pena non avere più il Canada?