“You’re Always Going to Need Oil” + Counterpoint/"Avremo sempre bisogno del petrolio"+ Controcanto

Life on the Edge of the Bakken Boom/Vita ai margini del boom del Bakken

As you cross from Alberta into Saskatchewan, driving through the vast plains beneath endless skies, you first glimpse them sporadically, then more systematically, in full-fledged, orderly formations like silent rows of obedient steel soldiers—they are the oil pump-jacks, also known as “nodding donkeys,” for their distinctive, repetitive bowing motion.

The encounter with these modern-day slaves of oil production sparked our curiosity. When the opportunity arose, we asked one of the men working on their maintenance about the activity surrounding them and the economy they feed into.

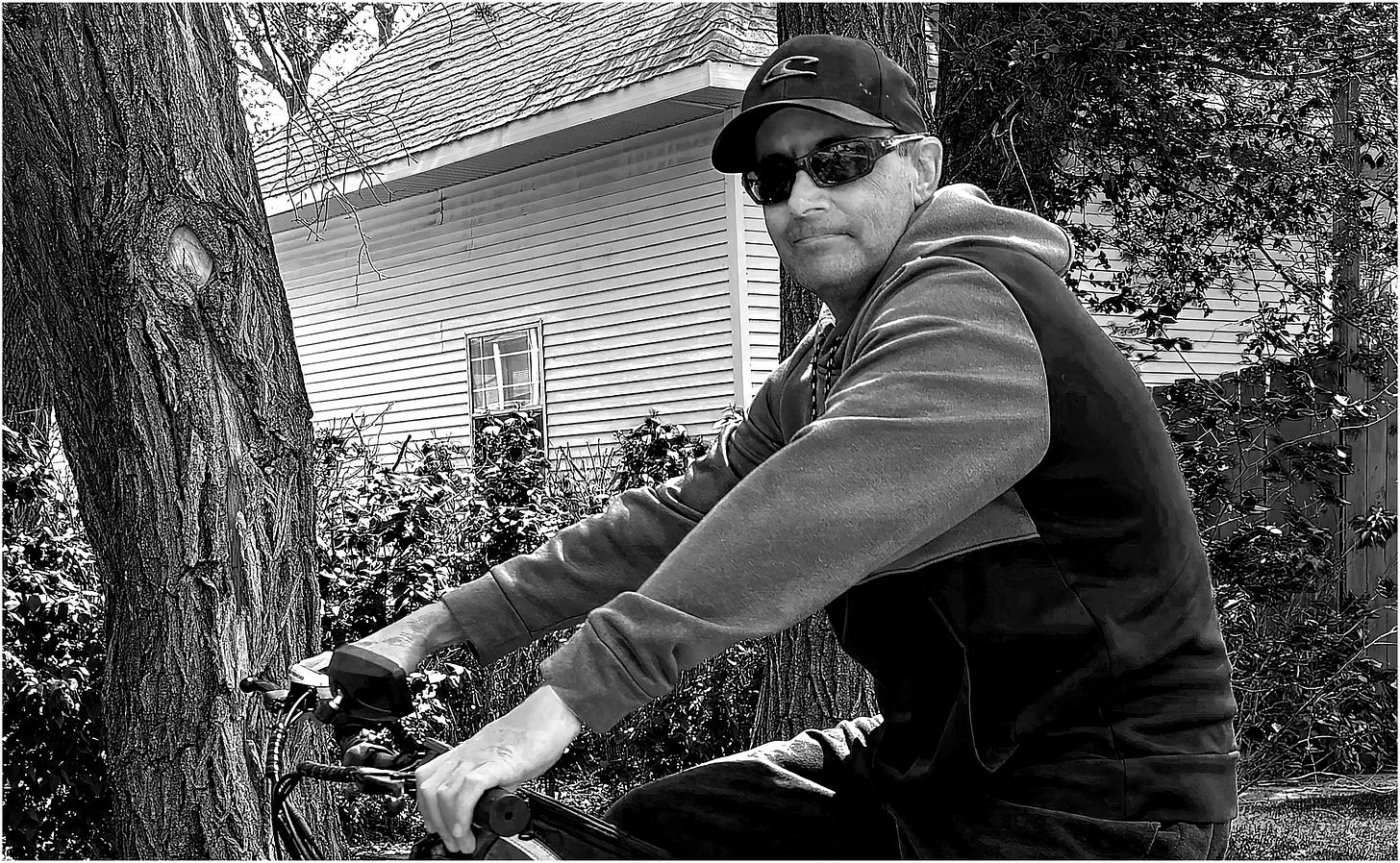

We met Stu Ryder in front of his home in the small town of Arcola (population 657), which, as he recalls, briefly stirred from its rural slumber about fifteen years ago, when the Bakken field roared to life during Saskatchewan’s oil boom.

A jack pumping oil among the cattle on a farmer’s land near Arcola, SK (Video: Arianna Dagnino)

Q: Where are you originally from?

I’m from Lampman, about half an hour south of here.

Q: What triggered the oil boom in this area, 15 years ago?

The oil price shot up—over $100 a barrel, maybe $110 or $115. That’s when they really started drilling. But it didn’t last long. Prices dropped, and things settled down again. I wouldn’t call it a depression—it just normalized.

Q: What exactly do you do in the oil field?

I work in maintenance. We use big tractors to haul equipment up into the hills when it’s muddy—because even when it rains, oil has to be hauled. We pull trucks in and out with tractors.

Q: And all these pump jacks we see around—are they connected underground?

Yes, all connected by underground pipes. Different companies own them. GB Construction handles some of the infrastructure, and Integrity Maintenance takes care of the pump jacks—the packing around the rods and such.

Q: Are these companies Canadian?

Oh yeah, they’re all Canadian.

Q: Does the government play a role in operations here?

Not really. I mean, maybe in setting the oil price, but the drilling and day-to-day work is private.

Q: Are there concerns about fracking or the water table here?

People do complain about fracking—it’s definitely happening here, not just in the U.S. I used to work on frack jobs, sitting on a back truck overnight just in case something went wrong. But I haven’t heard of any aquifer issues around here.

Q: Still, we noticed that people here often drink bottled water. Why is that?

Some do, but a lot still drink from the tap. It’s just that sometimes the water’s salty. When they drill, the first thing they usually hit is saltwater. You’ve got to drill deeper to get past that to reach the oil.

Q: Do you believe this region will continue to profit from oil?

Absolutely. The Bakken field is massive. I don’t think it’ll run out in my lifetime—or even the next couple.

Q: What about renewable energy—wind turbines, for instance? Are they a threat to oil?

Not around here. There are some turbines up in the hills. A crew from Nova Scotia was working there. But wind power is more expensive, and it doesn’t hurt us. You’re always going to need oil.

Q: How important is the oil industry for employment here?

It’s huge. If the oil field shut down, we’d be left with just farming—and that wouldn’t be enough. Those are the only two industries around here: oil and agriculture. And even farmers benefit from oil, since many lease out their land for the pumpjacks.

Counterpoint: Art for the Land

“I moved here to basically monitor the activity that was happening—and that I knew would come—because when people see resources in the ground, they want them, right?”

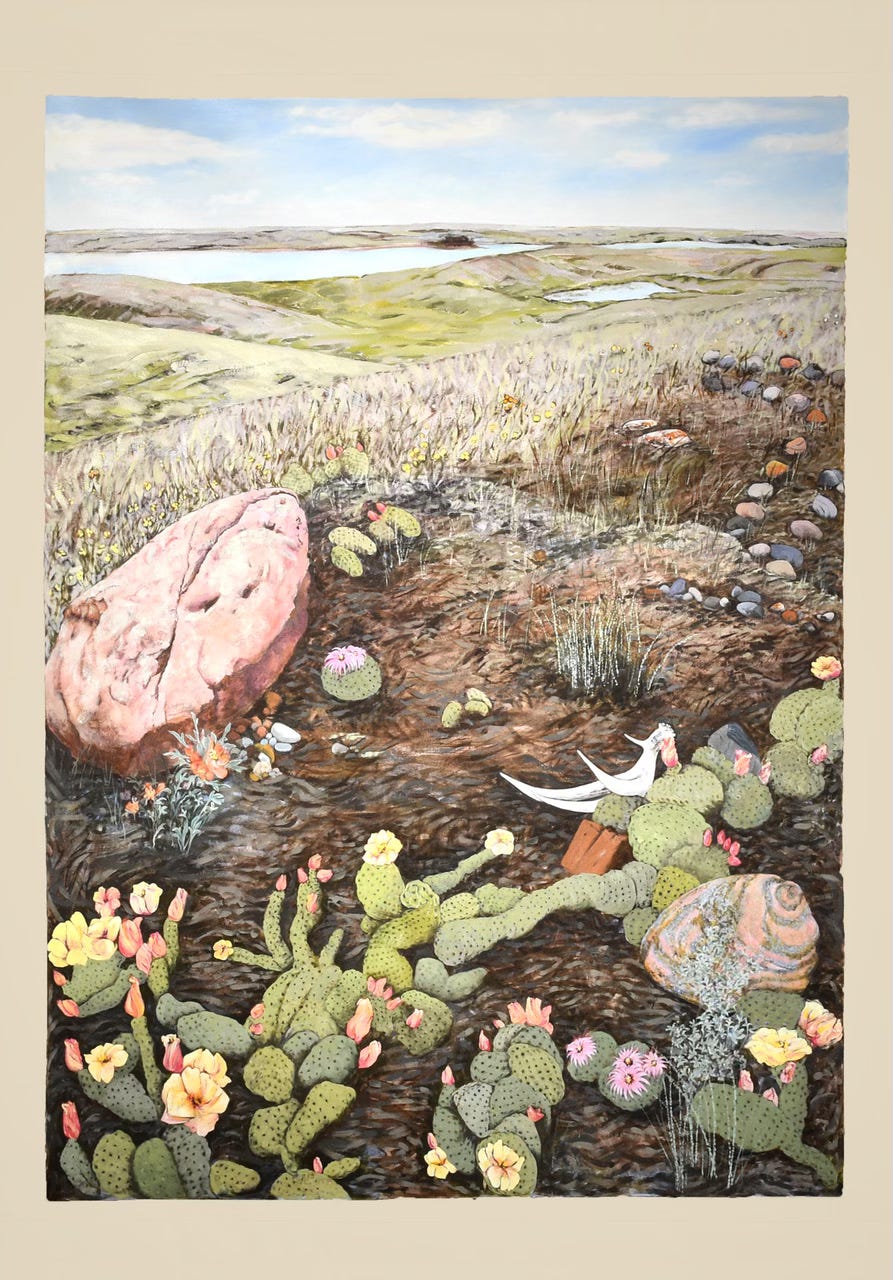

Not everyone is happy about the new rush to exploit Saskatchewan’s natural resources. Diana Chabros, an artist living in Val Marie, bordering the Grasslands National Park, SK is one such voice of concern. “Here in the southwest, we have the Grasslands—a protected area. But now, just recently, there’s been talk of mining and oil drilling nearby.”

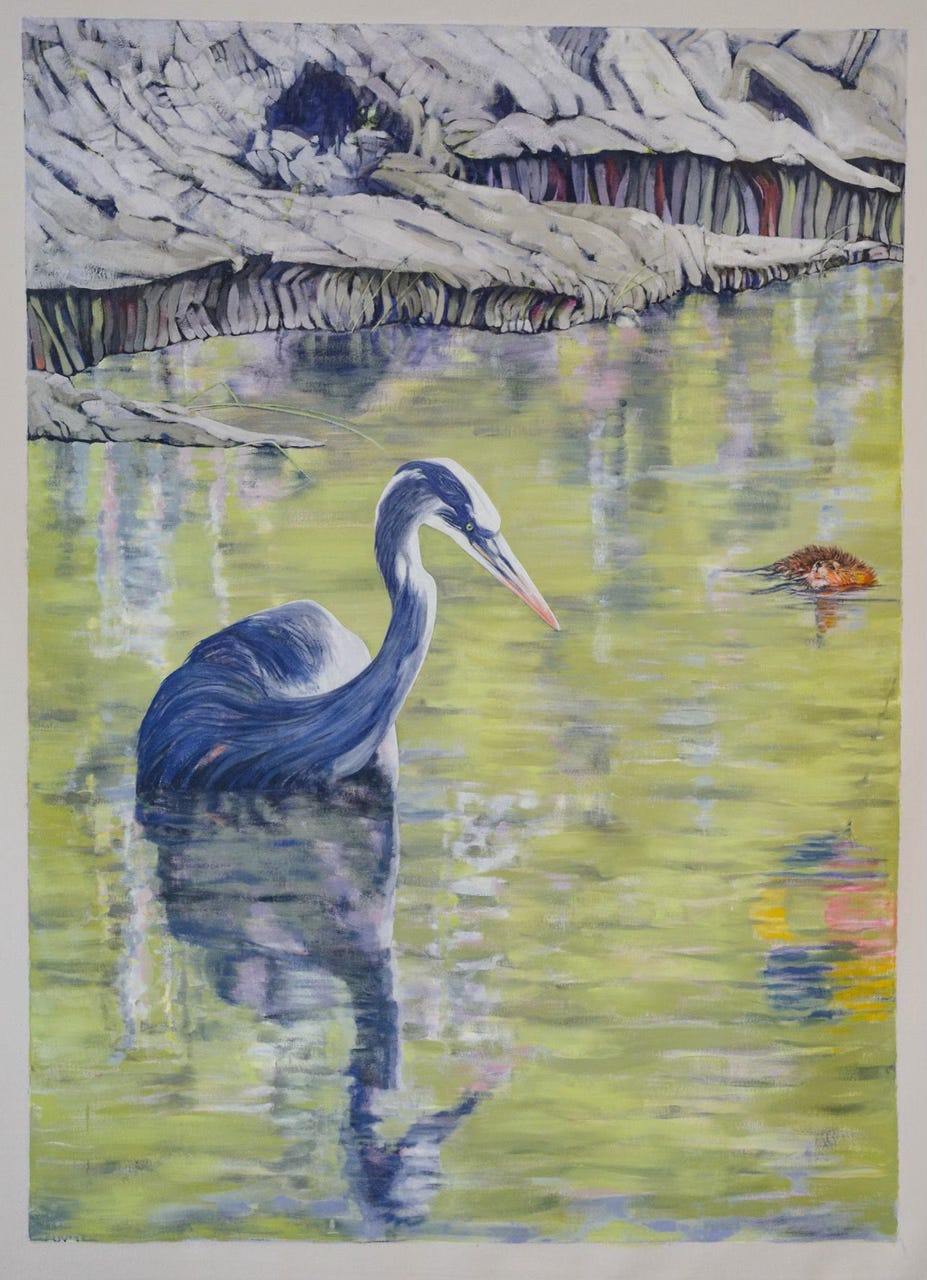

And now, helium: “We have one of the world’s largest helium reserves here in the southwest. Helium is a gas trapped underground, and extracting it is a dangerous process.” Chabros has used her painting Great Blue Heron on Helium (see picture below) to denounce this trend. “My work is intentionally dark. While I want to capture the beauty of this place, I also want to raise awareness. If that comes across as dark, so be it. A lot of people are put off by artists who try to spark awareness. People want art in their lives, but they don’t necessarily want to be reminded of their responsibilities.”

Quite a few in the area seem not to appreciate that call to responsibility. “People around here have different views, and many don’t respond well to strong conservationist stances,” says Chabros. “And I get that—there have been times when conservationists came through, pointing fingers at ranchers.” And, all in all, the artist who moved to Arcola thirteen years ago with her nehiyaw (Cree partner), singer/songwriter Joseph Naytowhow, prefers a more careful approach. “While I’m critical of many of the choices being made about the land, I think the local farmers are doing a good job preserving it. There’s no question: they really know the land.”

"Avremo sempre bisogno del petrolio" + Controcato

Superato il confine tra Alberta e Saskatchewan, mentre si attraversano le grandi pianure dai cieli senza fine, cominciano ad apparire. Prima isolati, poi in maniera sempre più sistematica, allineati come soldatini d’acciaio in silenziosa parata: si tratta dei “pumpjacks”, le pompe di estrazione petrolifera note anche come “nodding donkeys” (asinelli che annuiscono), per via del loro caratteristico inchinarsi ritmicamente verso terra.

La vista di questi schiavi meccanici dell’industria estrattiva ha acceso la nostra curiosità. Così, quando se n’è presentata l’occasione, abbiamo fatto alcune domande a uno degli uomini che ne cura la manutenzione, per avere qualche informazione sul loro funzionamento e sull’economia che vi ruota attorno.

Abbiamo incontrato Stu Ryder (48 anni) davanti alla sua casa, nel villaggio di Arcola (657 abitanti) che, come ricorda lui stesso, si è brevemente risvegliato dal suo torpore rurale circa quindici anni fa, quando il giacimento di Bakken è entrato in piena attività alimentando il boom petrolifero del Saskatchewan.

D: Di dove sei originario?

Vengo da Lampman, a circa mezz’ora da qui, a sud.

D: Cosa ha innescato il boom del petrolio in questa zona, quindici anni fa?

Il prezzo del petrolio era schizzato alle stelle—oltre i 100 dollari al barile, forse anche 110 o 115. È stato allora che hanno davvero iniziato a trivellare da queste parti. Ma non è durato a lungo: i prezzi sono scesi e tutto si è un po’ ridimensionato. Non parlerei di crisi vera e propria, direi piuttosto che le cose sono tornate alla normalità.

D: Di cosa ti occupi esattamente?

Mi occupo della manutenzione dei pozzi. Quando il terreno è fangoso, usiamo grandi trattori per trasportare l’attrezzatura sulle colline—perché anche con la pioggia, il petrolio va comunque estratto e trasportato. Con i trattori trainiamo dentro e fuori i camion.

D: E tutte queste pompe che vediamo in giro, sono collegate sottoterra?

Sì, sono tutte collegate da tubature sotterranee. Appartengono a compagnie diverse. La GB Construction si occupa di parte delle infrastrutture, mentre la Integrity Maintenance gestisce la manutenzione delle pompe, delle guarnizioni attorno alle aste e di altri componenti.

D: Queste compagnie sono canadesi?

Assolutamente sì, sono tutte canadesi.

D: Il governo ha un ruolo nelle operazioni?

Non proprio. Forse per quanto riguarda il prezzo del petrolio, ma le trivellazioni e il lavoro quotidiano sono gestiti da compagnie private.

D: Ci sono preoccupazioni relative al fracking o per le falde acquifere?

È un dato di fatto: anche qui si fa fracking, non solo negli Stati Uniti e c’è chi si lamenta per questo. Io stesso ho lavorato in operazioni di fratturazione, stando su un camion di supporto durante la notte, pronto a intervenire in caso di problemi. Tuttavia, non ho mai sentito parlare di contaminazioni delle falde acquifere da queste parti.

D: Però abbiamo notato che molta gente qui beve acqua in bottiglia. Perché?

Alcuni sì, ma c’è anche chi continua a bere l’acqua del rubinetto. Il problema è che, a volte, l’acqua è un po’ salata. Quando si trivella, la prima cosa che si incontra è proprio l’acqua salmastra. Bisogna scendere molto più in profondità per superarla e arrivare al petrolio.

D: Pensi che questa regione continuerà a trarre profitto dal petrolio?

Assolutamente sì. Il giacimento di Bakken è enorme. Non credo che si esaurirà, almeno non durante la mia vita.

D: E le energie rinnovabili, come le turbine eoliche, sono una minaccia per il petrolio?

Non da queste parti. Ci sono alcune turbine sulle colline, ci lavorava una squadra venuta dalla Nuova Scozia. Ma l’energia eolica costa di più e non ci crea problemi. Il petrolio ci servirà sempre.

D: Quanto è importante l’industria petrolifera per l’occupazione qui?

È fondamentale. Se l’attività petrolifera si fermasse, qui resterebbe solo l’agricoltura—e non sarebbe sufficiente. Le due colonne portanti dell’economia locale sono il petrolio e l’agricoltura. E attenzione: anche gli agricoltori traggono profitto dal petrolio, perché molti affittano i loro terreni per l’installazione delle pompe.

Anche gli agricoltori traggono vantaggio dal petrolio, poiché molti affittano i loro terreni alle compagnie petrolifere per l’installazione delle pompe di estrazione (Video: Arianna Dagnino)

Controcanto: Arte per la terra

“Mi sono trasferita qui, in pratica, per monitorare l’attività che stava già avvenendo—e che sapevo sarebbe arrivata—perché quando la gente sa che nel sottosuolo ci sono risorse, le vuole, giusto?

Non tutti accolgono con favore la nuova corsa allo sfruttamento delle risorse naturali in Saskatchewan. Diana Chabros, artista residente a Val Marie, ai bordi del Grasslands National Park, è una di queste voci critiche. “Qui, nel sud-ovest, abbiamo le Grasslands—un’area protetta. Eppure, di recente, si è cominciato a parlare di attività estrattive e trivellazioni petrolifere nelle vicinanze.”

Ora entra in gioco anche l’elio: “Questa zona ospita una delle riserve di elio più grandi al mondo. È un gas intrappolato nel sottosuolo e la sua estrazione è un processo pericoloso.”

Con il suo dipinto Great Blue Heron on Helium, Chabros ha voluto denunciare questa nuova tendenza. “Le mie opere sono volutamente cupe. Voglio cogliere la bellezza di questo luogo, certo, ma anche sensibilizzare le persone. Se questo viene percepito come oscuro, pazienza. Molti si infastidiscono quando gli artisti cercano di stimolare una presa di coscienza. La gente vuole l’arte nella propria vita, ma non sempre vuole essere messa di fronte alle proprie responsabilità.”

Non tutti nella zona apprezzano questo invito alla responsabilità. “La gente da queste parti ha opinioni diverse, e molti non reagiscono bene a posizioni ambientaliste troppo rigide. E lo capisco — ci sono stati momenti in cui i conservazionisti sono arrivati qui puntando il dito contro gli allevatori.”

In definitiva, l’artista — trasferitasi ad Arcola tredici anni fa insieme al suo compagno Cree, il cantautore Joseph Naytowhow — preferisce un approccio più misurato: “Pur criticando molte delle scelte fatte in merito all’uso del suolo, penso che gli agricoltori locali stiano facendo un buon lavoro nel preservarlo. Su questo non c’è dubbio: conoscono la terra.”