A Conversation with Chief Louie/Una conversazione con Chief Louie

"Every Decade Brings Change"/“Ogni decennio porta con sé dei cambiamenti”

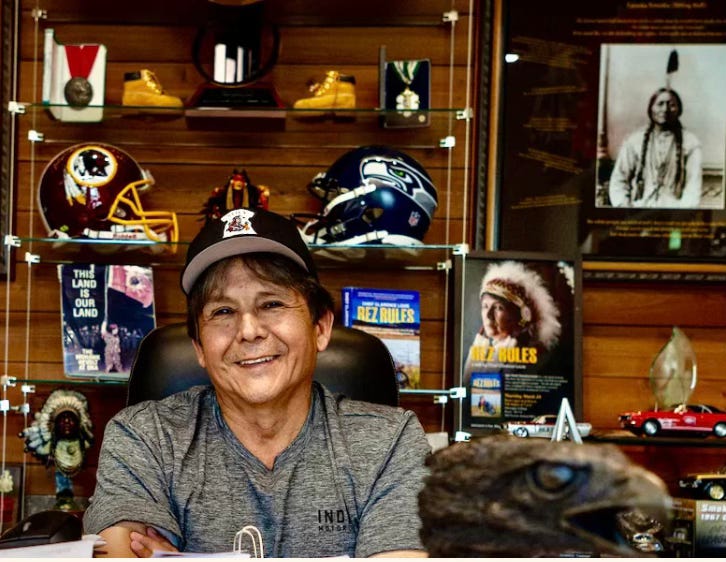

We began our trans-Canada journey by acknowledging that we would be crossing the traditional territories of the First Nations. On the first leg of our eastward itinerary, we therefore met with Chief Clarence Louie, leader of the Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB), whose reserve is located a five-hour drive (408 km) from Vancouver, in British Columbia.

Chief Clarence Louie has served as the elected leader of the Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB) for over 35 years. Renowned across Canada and internationally for his leadership in economic development and Indigenous self-determination, he has transformed the OIB into one of the most economically successful First Nations communities in the country. With unflinching clarity and humour, Chief Louie speaks of resilience, sovereignty, and what it means to live as an Indigenous person in today’s Canada.

Q: Can you share what the land means to you and to the people of your community?

Chief Clarence Louie:

To us, the land is not just a piece of real estate — it’s our identity, our history, and our future. Our ancestors lived across these territories long before there were borders, provinces, or countries called Canada or the United States. Today, we live on Indian reserves — small chunks of land compared to what we once had. These “reserves” were created in the 1870s when our people couldn’t read or write English, and colonial governments put us into confined spaces through policies designed to control and assimilate us.

What’s important to understand is that this wasn’t unique to Canada. It happened on both sides of the border. Canada calls them Indian reserves; the U.S. calls them Indian reservations. Canada had residential schools; the U.S. had boarding schools. These were the same institutions with the same goals: to erase Indigenous culture, language, and identity. It’s part of a broader colonial legacy rooted in the British Empire, whether you’re talking about Canada, Australia, New Zealand, or South Africa.

Despite all that, we hold onto our land and title rights. We haven’t given up our hunting, fishing, or taxation rights. We still claim them, and we still live by them. The land still belongs to us in spirit, and we continue to fight for it in practice.

Q: In the face of such challenges, what do you believe keeps your community strong and resilient?

We stay strong because of our connection to our history and our insistence on being recognized as the original people of this land. We’ve had to survive policies that tried to erase us — forced relocation, cultural suppression, economic marginalization. But through it all, we held onto our traditions and our sense of belonging. Today, that strength is also tied to our growing economic power. When you have economic influence, people listen — including governments and corporations. That wasn’t always the case.

Q: How do you continue to build that strength and resilience today, especially for the future?

Economic development is a big part of it. We’re building our own businesses, investing in our communities, creating jobs for our people. That gives us independence. And with that comes political influence.

What I've noticed with white people is that, once you have economic power, you get their political attention.

We now have a seat at the table when major decisions are made — about pipelines, natural resources, and infrastructure projects.

We also work within the legal and political systems. Our people are no longer getting locked up when fighting over treaty rights and fishing and hunting rights.

We’re no longer being thrown in jail like we were in the ’60s and ’70s for standing up for treaty rights.

Today, we take those fights to court, and we negotiate with provincial and federal governments. It’s a long process, but there’s progress. Every province now has a Minister of Indigenous Relations — that wasn’t even on the radar a generation ago. These changes don’t happen overnight. They take decades. But they do happen.

Q: What are your greatest hopes — and perhaps your concerns — when you think of the younger generation in your community?

I hope young people understand the sacrifices made by those before them. I hope they carry on the fight — not just politically, but culturally and economically. We need them to know their rights, know their history, and believe in their future. At the same time, I know that being young means being distracted. In your twenties, you just want to party, play sports, and have fun. That’s natural — I was the same way. But eventually, you grow into more responsibility, more awareness.

Q: In your view, how can First Nations people participate in wider Canadian society without losing touch with their traditions and values?

It’s possible to participate in Canadian society without losing who you are. Many of us grew up in these systems — schools, workplaces, politics — but we never stopped being Indigenous. We learned to navigate these institutions while holding onto our traditions.

We live in a world built on British colonial systems, whether we’re in Canada or the U.S., and we’ve had to adapt. But adaptation doesn’t mean assimilation.

We still practice our ceremonies. We still speak our languages. We still fight for our land. What’s different now is that we have tools and opportunities that weren’t available before. We use media, the courts, and economic leverage to make our voices heard. At the federal and provincial level they see that, you know, these Native people have political muscle, and now with our economic development, we're having an economic power that we didn't have before.

And it works — when you can affect pipelines, you can affect policy. People start to listen.

The relationship with Canada is still far from perfect, and probably never will be. But it’s better than it was. And if you look back, you’ll see that progress doesn’t happen year to year — it happens decade by decade. You change in your 40s from who you were in your 30s. In your 60s, you see things differently than you did in your 50s. That’s true for individuals, and it’s true for nations. We have to keep moving forward, decade by decade.

Q: From your perspective, what do you wish white Americans and Canadians better understood — or could learn — from First Nations ways of life?

That the natives aren't going away peacefully or quietly and just being, you know, absorbed into the American and Canadian system. We are to a great degree, but I’d like them to understand that we see the world through a lens of responsibility — to the land, to our families, to the next seven generations.

It’s not just about taking from the earth or chasing profit. It’s about balance, about giving back, and about recognizing that everything is connected. That’s a lesson we’ve held onto for thousands of years.

Another value is community. Our strength is not in how much you can do alone, but how you take care of your people, especially the elders and the youth. If Canadians and Americans understood that deeper sense of community and stewardship, we’d all be better off — environmentally, socially, and spiritually.

Una conversazione con Chief Louie

Abbiamo iniziato il nostro viaggio attraverso il Canada riconoscendo che avremmo attraversato i territori tradizionali delle Prime Nazioni (First Nations).1 Così, nella prima tappa del nostro itinerario verso est, abbiamo incontrato Chief Clarence Louie, il capo della Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB), la cui riserva si trova a cinque ore d’auto da Vancouver (408 km), nella Columbia Britannica..

Louie è alla guida dell’OIB da oltre 35 anni. Riconosciuto in tutto il Canada e a livello internazionale per la sua leadership nello sviluppo economico e nell’autodeterminazione delle popolazioni indigene, ha trasformato la sua comunità in una delle Prime Nazioni di maggior successo economico nel Paese. Con pacata chiarezza e un pizzico di umorismo, Chief Louie parla di resilienza, sovranità e di cosa significhi vivere oggi come persona indigena in Canada.

D: Può raccontarci che significato ha la terra per lei e per la sua gente?

Chief Louie: Per noi, la terra è tutto. Non è solo una proprietà immobiliare — è la nostra identità, la nostra storia, il nostro futuro. I nostri antenati hanno vissuto su questi territori molto prima che esistessero confini, province o Stati chiamati Canada o Stati Uniti. Oggi viviamo nelle riserve indiane — pezzi di terra molto più piccoli rispetto a quelli che avevamo un tempo. Queste riserve furono create negli anni 1870, quando la nostra gente non sapeva leggere né scrivere in inglese, e i governi coloniali ci costrinsero in spazi ristretti attraverso politiche pensate per controllarci e assimilarci.

È importante capire che non si tratta di qualcosa di esclusivo del Canada. È successo da entrambi i lati del confine. Il Canada le chiama “riserve indiane”, gli Stati Uniti “riserve indiane”. Il Canada aveva le scuole residenziali, gli Stati Uniti le boarding schools. Erano le stesse istituzioni con gli stessi obiettivi: cancellare la cultura e l’identità indigene. Fa parte di un’eredità coloniale più ampia, radicata nell’Impero britannico, che troviamo in Canada, Australia, Nuova Zelanda o Sudafrica.

Nonostante tutto questo, continuiamo a rivendicare i nostri diritti territoriali. Non abbiamo rinunciato ai nostri diritti di caccia, pesca o tassazione. Li rivendichiamo ancora e continuiamo a viverli. La terra ci appartiene ancora nello spirito, e continuiamo a lottare per essa, concretamente.

D: Di fronte a sfide così grandi, cosa crede mantenga forte e resiliente la sua comunità?

Chief Louie: Restiamo forti grazie al legame con la nostra storia e alla determinazione di essere riconosciuti come i popoli originari di questa terra. Abbiamo dovuto sopravvivere a politiche pensate per cancellarci — dallo spostamento forzato alla repressione culturale, alla marginalizzazione economica. Ma nonostante tutto, abbiamo conservato le nostre lingue, le nostre tradizioni e il senso di appartenenza. Oggi, quella forza è alimentata anche dalla nostra crescente capacità economica.

Quello che ho notato dei bianchi è che, una volta che hai potere economico, ottieni la loro attenzione politica.

Quando hai influenza economica, la gente ti ascolta — inclusi governi e aziende. Non è sempre stato così.

D: Come si assicura che la sua comunità si mantenga forte e resiliente, anche di fronte alla sfide del futuro?

Chief Louie: Lo sviluppo economico è una componente fondamentale. Stiamo costruendo le nostre imprese, investendo nelle nostre comunità, creando posti di lavoro per la nostra gente. Questo ci dà indipendenza. E con essa arriva anche l’influenza politica. Ora abbiamo un posto al tavolo quando si prendono decisioni importanti — su oleodotti, risorse naturali, progetti infrastrutturali.

Lavoriamo anche all’interno dei sistemi legali e politici, andando in tribunale invece che in prigione.

In passato, la nostra gente veniva incarcerata per aver difeso i diritti dei trattati. Oggi portiamo quelle battaglie in tribunale e negoziamo con i governi provinciali e federali.

È un processo lungo, ma si vedono dei progressi. Oggi ogni provincia ha un Ministro per le Relazioni con le Popolazioni Indigene — una cosa che una generazione fa nemmeno si immaginava. Questi cambiamenti non avvengono dall’oggi al domani. Ci vogliono decenni. Ma accadono.

D: Quali sono le sue speranze — e magari anche le sue preoccupazioni — pensando ai giovani della sua comunità?

Chief Louie: Spero che i giovani comprendano i sacrifici fatti da chi li ha preceduti. Spero che portino avanti la lotta — non solo sul piano politico, ma anche culturale ed economico. Devono conoscere i loro diritti, la loro storia, e credere nel loro futuro. Allo stesso tempo, so che da giovani si tende a distrarsi. A vent’anni vuoi solo divertirti, fare sport, andare alle feste. È naturale — anch’io ero così. Ma col tempo si cresce, si assumono più responsabilità, si sviluppa più consapevolezza. La mia speranza è che questo processo avvenga prima che dopo, perché il nostro futuro dipende da loro.

D: Secondo lei, come possono le persone delle Prime Nazioni partecipare alla società canadese senza perdere il legame con le proprie tradizioni e i propri valori?

Chief Louie: È possibile far parte della società canadese senza perdere se stessi. Molti di noi sono cresciuti all’interno di questi sistemi — scuole, luoghi di lavoro, politica — ma non abbiamo mai smesso di essere indigeni. Abbiamo imparato a navigare in queste istituzioni mantenendo vive le nostre tradizioni. Viviamo in un mondo costruito su sistemi coloniali britannici, sia in Canada che negli Stati Uniti, e abbiamo dovuto adattarci. Ma adattamento non significa assimilazione.

Continuiamo a praticare le nostre cerimonie. Continuiamo a parlare le nostre lingue. Continuiamo a lottare per la nostra terra. La differenza oggi è che abbiamo strumenti e opportunità che prima non avevamo. Usiamo i media, i tribunali e la leva economica per farci sentire.

E funziona — se puoi influenzare un oleodotto, puoi influenzare le politiche. La gente inizia ad ascoltare.

Il rapporto con il Canada è ancora lontano dall’essere perfetto, e probabilmente non lo sarà mai. Ma è migliore di un tempo. E se guardi indietro, vedi che i progressi non si misurano anno per anno — si misurano decennio dopo decennio. Cambi a quarant’anni rispetto a com’eri a trenta. A sessant’anni vedi le cose diversamente da come le vedevi a cinquanta. È vero per gli individui, ed è vero per le nazioni. Dobbiamo continuare ad andare avanti, decennio dopo decennio.

D: Dal suo punto di vista, cosa vorrebbe che canadesi e statunitensi bianchi capissero — o imparassero — dal modo di vivere delle Prime Nazioni?

Chief Louie: Vorrei che capissero che noi vediamo il mondo attraverso la lente della responsabilità — verso la terra, verso le nostre famiglie, verso le prossime sette generazioni.

Non si tratta solo di prendere dalla terra o di inseguire il profitto. Si tratta di equilibrio, di restituzione, e di riconoscere che tutto è connesso. Questa è una lezione che conserviamo da migliaia di anni.

Un altro valore fondamentale è la comunità. La nostra forza non sta in ciò che puoi fare da solo, ma in come ti prendi cura del tuo popolo, soprattutto degli anziani e dei giovani. Se canadesi e americani comprendessero questo senso profondo di comunità e responsabilità, tutti ne trarremmo beneficio — a livello ambientale, sociale e spirituale.

“Prime Nazioni” (First Nations) indica i popoli indigeni che non appartengono ai gruppi Inuit o Métis. Il termine è nato negli anni ’80 per sostituire “Indian” (considerato obsoleto o offensivo) e riconoscere la sovranità e l’identità distintiva di centinaia di comunità e nazioni autoctone diverse, ciascuna con la propria lingua, cultura e sistema di governo tradizionale.